Via

#FucktheNRA

Friday, 28 December 2012

Fontella Bass RIP

'Rescue Me' singer Fontella Bass dies aged 72

One of my gig going highlights was seeing Fontella perform with hubby Lester Bowie's Brass Fantasy at the Bracknell Jazz Fest in the early eighties...wish I still had my recording of that!Vale Gerry Anderson

Lady Penelope comes home late from a

party:

Lady Penelope: "Parker, take off my coat"

Parker: "Yes m'lady"

LadyP: "Parker, take off my dress and shoes"

Parker: "Yes m'lady"

LadyP: "Parker, take off my bra and panties..."

Parker: "Yes m'lady"

LadyP: " ...and don't let me EVER catch you wearing them again"

My childhood would have been totally different without you

Lady Penelope: "Parker, take off my coat"

Parker: "Yes m'lady"

LadyP: "Parker, take off my dress and shoes"

Parker: "Yes m'lady"

LadyP: "Parker, take off my bra and panties..."

Parker: "Yes m'lady"

LadyP: " ...and don't let me EVER catch you wearing them again"

My childhood would have been totally different without you

Portraits of Albanian Women Who Have Lived Their Lives As Men

For her project Sworn Virgins of Albania, photographer Jill Peters

visited to the mountain villages of northern Albania to capture

portraits of “burneshas,” or females who have lived their lives as men

for reasons related to their culture and society.

Many of the women assumed their male identities from an early age as a way to avoid the old codes that governed the tribal clans, which stated that women were the property of their husbands. Peters explains,

Many of the women assumed their male identities from an early age as a way to avoid the old codes that governed the tribal clans, which stated that women were the property of their husbands. Peters explains,

The freedom to vote, drive, conduct business, earn money, drink, smoke, swear, own a gun or wear pants was traditionally the exclusive province of men. Young girls were commonly forced into arranged marriages, often with much older men in distant villages. As an alternative, becoming a Sworn Virgin, or ‘burnesha” elevated a woman to the status of a man and granted her all the rights and privileges of the male population. In order to manifest the transition such a woman cut her hair, donned male clothing and sometimes even changed her name. Male gestures and swaggers were practiced until they became second nature. Most importantly of all, she took a vow of celibacy to remain chaste for life. She became a “he”. This practice continues today but as modernization inches toward the small villages nestled in the Alps, this archaic tradition is increasingly seen as obsolete. Only a few aging Sworn Virgins remain...

Youth - Beginning Of The World Dub Set Pt 2 (The King Is Dead, Long Live The King)

(Downwards arrow to download)

1. Killing Joke - Requiem (A Floating Leaf Always Reaches The Sea Mix)

2. Mark Stewart - Method To The Madness Dub (Youth and Mark's Dub Mix)

3. Killing Joke - Labryrinth Dub

4. Youth vs Brother Culture - Final Push Dub Attack

5. Dahab Express (Youth's Special Edit)

6. The Orb Featuring David Gilmour - Metallic Spheres (Gaudi Remix)

7. White Rainbow - Awakening

8. Poly Styrene - Black Christmas (Khan Remix)

9. Mark Stewart - Attack Dogs (Featuring Primal Scream) (Youth and Mark's Dub Mix)

10. Killing Joke - Money Is Not Our God (Babylon Dub)

11. Killing Joke - Democracy (Russian Tundra Mix) (Orb Remix)

12. Brian Barritt vs Youth - Cosmic Courier

13. Killing Joke - Tomorrow's World (Urban Primitive Dub)

14. White Noise - Love Without Sound

15. Killing Joke - This World Hell (Cult Of Youth Ambient Samsara Dub Mix)

16. Mark Stewart - Apocalypse Dub (Feat. Daddy G) (Youth and Mark's Dub Mix)

17. Richard Thompson - The Calvary Cross (Intro) vs Refused - Refused Are Fucking Dead

18. Youth - Global Chant (Acapella Dub)

19. Suns Of Arqua - Raga 4 (Youth Ambient Mix)

Bonus:

Youth's End Of The World Dub Mix Set

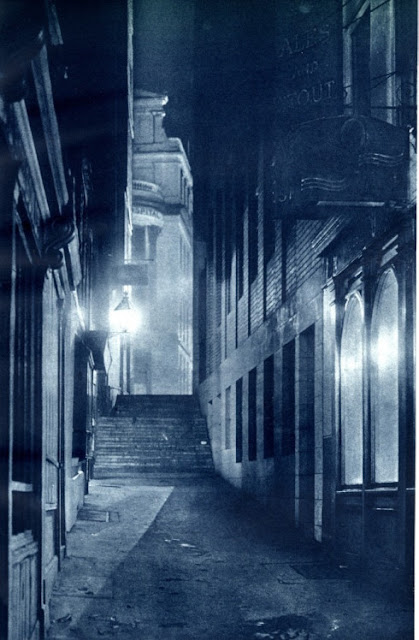

The London Nobody Knows

In the wholly terrestrial 1980s, I would scour and dogear the Radio and TV Times the day they came out, looking for rare showings of great films and archive oddities. Channel 4 made life easy with Truffaut, British new wave, or Marx Brothers seasons. The real plums, though, could often be hidden in the ITV - or Thames, round our way - schedules, maybe at one in the morning, maybe at three in the afternoon.

It was the latter slot that broadcast The London Nobody Knows, a 1967 documentary stroll around the city with James Mason. No horseguards, no palaces, but Islington's Chapel Market, pie shops, and Spitalfields tenements. Carnaby chicks and chaps, the 1967 we have been led to remember, are shockingly juxtaposed with feral meths drinkers, filthy shoeless kids, squalid Victoriana. Camden Town still resembles the world of Walter Sickert. There is romance and adventure, but mostly there is malnourishment. London looks like a shithole.

The film was directed by Norman Cohen and based on a book by Geoffrey Fletcher. When our band, Saint Etienne, came to making our first film, Finisterre, Fletcher was our mentor, The London Nobody Knows our first point of reference. Fletcher is the great forgotten London writer. He went to the Slade School of Art and drew sketches for the Guardian and the Daily Telegraph, where he recorded the rapidly changing capital in a column called London Day by Day.

The London Nobody Knows was first printed in 1962, and he followed it with a string of books (London After Dark, Pearly Kingdom, The London Dickens Knew) which all covered similar ground. But being written in a style equal parts Max Beerbohm and Oscar Wilde, sharpness and melancholy, it hardly mattered. The only noticeable change was in his growing irascibility with the passing years.

It is hard to believe he hasn't been an influence on contemporary Londonographers. Like Iain Sinclair, he frequents areas where "the kids swarm like ants and there are dogs everywhere": Hoxton, Camberwell, Whitechapel. Yet he never plays the inverted snob and adores Hampstead. Once, at a fair on the Heath, he overheard a man saying that Hampstead wasn't thrilling enough. Fletcher reached over in the darkness and stuck an ice lolly down the back of his shirt.

Along with Peter Ackroyd, Fletcher shares a keen interest in public toilets, referring to himself as an "experienced conveniologist". Among his favourites are lavatories in Holborn where the attendant once kept goldfish in the water tank. And, like Ackroyd, he has an obsession with Hawksmoor: The London Nobody Knows was written at a time when one of his pentagram of churches - Christ Church, Spitalfields - was under threat of demolition. He relishes bad Gothic architecture and, again like Ackroyd, feels that London's past is ever-present - the spirit of Sherlock Holmes, Peter Pan, or Peter the Painter. Fact or fiction, or even just "the odour of London dinners". "In spite of the passage of time, one can feel a decided atmosphere," he reckons, in "mistressy Maida Vale" and in London's permanent "pleasing state of decay".

Fletcher was capturing London on the cusp, ordering his readers to look up as they walked along the street - because that "cardboard medievalism" or "early Oscar Wilde" (his shorthand for 1880s architecture) may be gone before long. And, thankfully, a lot of it has.

He is rarely sentimental ("the quick dull look of the true Londoner" sticks in the memory) but the music halls were a loss of particular sadness for him. In the film, James Mason walks around the ruins of the now-gone Bedford theatre in Camden, where Marie Lloyd was a regular performer and which Sickert frequently painted. Off the top of my head, the only music hall he mentions that is still standing is Harwood's Varieties on Pitfield Street, Hoxton - now some kind of warehouse. But it was the interiors that Fletcher found particularly enchanting and they are all gone. The remains are skeletons of "a vanished civilisation that will be as mysterious and incomprehensible in the coming time as Stonehenge".

Still, every so often you come across something that has survived into the 21st century. Cartwright Gardens, Bloomsbury, a down-at-heel crescent of lodgings and seedy hotels where Fletcher lived as an art student, has hardly changed since the 1940s. The view over to King's Cross and St Pancras from the brow of Pentonville Road still has an odd, windswept romanticism. James Smith's umbrella shop on New Oxford Street seemed a miraculous survivor in 1962, let alone 2003. And then there's Ely Place, ostensibly in Holborn but to this day officially part of Cambridgeshire.

Where Fletcher mourned the passing of the music halls, today it is the Italian caffs and milk bars of the 1950s and 1960s that are being wiped out in an unseemly rush. Eateries like the New Piccadilly on Denman Street (hanging on) and Presto on Old Compton Street (just expired) are central to the birth of British pop culture. Mimicking the author in his absence, I'll direct you to the wonderfully wooded Chalet on Grosvenor Street and the Copper Grill, near Liverpool Street, which has one of the most beautiful facades in London and is due to disappear next spring - relics as otherworldly now as Victorian oyster rooms must have seemed in the 1960s.

No question, Geoffrey Fletcher was obsessed with London, driven on by a mania for exploration. He considered it not in the least unhealthy, and compared it to Toulouse-Lautrec's obsession with Montmartre. It was his belief that "a man can do everything better in London - think better, eat and cheat better, even enjoy the country better". He desired a London of human proportions and worried that office blocks would wipe out the pie shops, Hawksmoor's churches, "the tawdry, extravagant and eccentric". Yet this hasn't happened and probably never will. He would always be able to find something to savour, something to sketch in a city that constantly evolves.

The GLC should have created a heritage job for him, to archive and catalogue the city's finest aberrations. Instead he has left us a stack of atmospheric, thrilling documents. "In England" he grumbled, "such things are almost always left to chance, and a few cranks." Geoffrey Fletcher would be pleased to know that the ambiguous melancholy of The London Nobody Knows has inspired a new generation of cranks.

Bob Stanley @'The Guardian' (2003)

Thursday, 27 December 2012

Brion Gysin Permutations Software

I wrote the software "Permutations" for the exhibition Brion Gysin: Dream Machine on display at The New Museum for Contemporary Art between July 7th and October 3rd 2010. This software is a "version" of the program developed by Ian Sommerville and Gysin in 1960 to permute poems. The original program ran on a Honeywell Series 200 model 120 computer. The version I wrote uses a modern programming language and hardware. While the materials used to produce the original permutation poems are in many ways quite different from my own, I have attempted to create a realization of the work that is sensitive to the original and its process. At the same time, it is a new version, a collaboration done in the spirit of an artist whose work provides a critique of conventional notions of authorship.

I believe it is in the spirit of the work to share copies of the software I wrote under the GNU General Public License. This license allows gives anyone the ability to download, run, alter, and share the software. The one requirement is that all future versions must be released under the GPL as well. You may download the software here or on github.

In closing, I want to thank The New Museum and specifically Kraus Family Curator Laura Hoptman and Assistant Curator Amy Mackie for their trust and support in completing this project. Thanks also to Doron Ben-Avraham, Manager of Information Technology at The New Museum for his help and advocacy.

Joseph Moore 2010

Documentation of Permutations also available on ubu.com

Via

(Thanx SJX!)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)