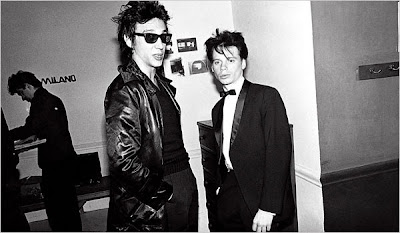

Richard Hell & James Chance (Photo: Julia Gorton)

Richard Hell & James Chance (Photo: Julia Gorton)Review of 'No Wave' byThurston Moore & Byron Coley

By BEN SISARIO

Published: June 12, 2008

@ 'NY Times'

Of all the strange and short-lived periods in the history of experimental music in New York, no wave is perhaps the strangest and shortest-lived.

Centered on a handful of late-1970s downtown groups like Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, DNA and James Chance’s Contortions, it was a cacophonous, confrontational subgenre of punk rock, Dadaist in style and nihilistic in attitude. It began around 1976, and within four years most of the original bands had broken up.

But every weird rock scene — and every era of New York bohemia — eventually gets its coffee-table book moment. This month Abrams Image is publishing “No Wave: Post-Punk. Underground. New York. 1976-1980,” a visual history by Thurston Moore and Byron Coley.

On Friday the book will be celebrated with an exhibition opening at KS Art, at 73 Leonard Street in TriBeCa, and, across the street at the Knitting Factory, the reunion of Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, whose blunt, aggressive songs had instrumentation so minimal that on its records the percussionist was sometimes credited as playing simply “drum.” Lydia Lunch, the former lead singer, is flying from Barcelona to play the show.

In the last year two other books have been published on no wave and overlapping periods of downtowniana: Marc Masters’s “No Wave” (Black Dog) and “New York Noise” (Soul Jazz), a collection of photographs by Paula Court.

“It was a little, blippy scene,” said Mr. Moore, the Sonic Youth guitarist and historian of underground rock. “It came out of the gate finished.”

With crisp black-and-white photographs and interviews with musicians and visual artists, the book is a loving reminiscence of a largely unheard period, as well as a look at a seedy, pre-gentrified Lower East Side. Most groups in the no wave scene — which also included Mars, the Theoretical Girls and the Gynecologists — left behind few recordings, and the compilation album that defined the genre, “No New York,” produced by Brian Eno in 1978, has never been legitimately issued on CD in the United States.

Despite its brief, blippy existence, no wave has had a broad and continued influence on noisy New York bands, from Sonic Youth and Pussy Galore in the 1980s to current groups like the Yeah Yeah Yeahs and the Liars. But the original no wavers saw themselves not as part of any rock continuum but a deliberate reaction against such an idea.

“A guitar player like Lydia Lunch was somebody who clearly was not coming out of any kind of tradition,” said Mr. Coley, a veteran rock critic. “She didn’t have a Chuck Berry riff in her.”

The rebelliousness came out in many ways, from song composition — nasty, brutish and short — to the movement’s name, a cynical retort to “new wave,” then emerging as a more palatable variation on punk. The looks were nerdy and androgynous (or, in Ms. Lunch’s case, menacingly oversexed).

The sound reflected the squalor and decay of downtown New York in the late ’70s.

“New York at that moment was bankrupt, poor, dirty, violent, drug-infested, sex-obsessed — delightful,” Ms. Lunch said by phone. “In spite of that we were all laughing, because you laugh or you die. I’ve always been funny. My dark comedy just happens to scare most people.”

Mr. Moore and Mr. Coley’s book emphasizes the major role that women had in the scene. Besides Ms. Lunch, they included Pat Place of the Contortions, Ikue Mori of DNA and Nancy Arlen of Mars, as well as impresario-scenesters like Anya Phillips. Many photographs were taken by women, among them Julia Gorton and Stephanie Chernikowski.

Ms. Gorton, who was a student at the Parsons School of Design in the late ’70s and now teaches there, said that everyone in the no wave circle knew one another. “There were a lot of late nights, a lot of pitchers, a lot of Polaroids,” she said.

The book’s genesis was two years ago when Mr. Moore heard that Abrams, which published “CBGB & OMFUG: Thirty Years From the Home of Underground Rock” in 2005, was considering a book on no wave, with a broad and multidisciplinary approach.

Mr. Moore and Mr. Coley, who said they had been considering a no wave book for years, rushed to the Abrams office to pitch their idea, which would instead have a narrow focus, excluding everything that did not meet their strict definition of no wave.

A restrictive approach to one of the most obscure periods of rock music would seem to limit a book’s audience. But Tamar Brazis, who edited both books, said there was enough interest in the period to justify the “No Wave” book, and that the depth of Mr. Moore and Mr. Coley’s knowledge bowled her over. The CBGB book, she said, has sold nearly 40,000 copies, an impressive figure for an art book, and she added that Abrams has similar expectations for “No Wave.”

Mr. Moore said that only a narrow definition would fit the genre, which was so contrary in its sound and attitude that too much outside context would dilute its impact.

Foreword by Lydia Lunch & excerpt

HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment